The process for creating a reduction linoprint is something a lot of people have difficulty getting their head round. (Heck, sometimes it confuses me…and it’s what I do for a living). The most basic explanation is that a single piece of lino is carved away in successive layers which are printed over each other to create an image. Where the lino has been carved away, no more ink will touch that part of the paper, so those bits of the image will retain only the colour(s) received so far, while uncarved areas will be overprinted with the next layer of ink.

That’s the simple version. The more complicated version includes that you don’t have to apply ink to the whole block for each layer, and that inks can be translucent or opaque so will behave differently when layered over previous colours.

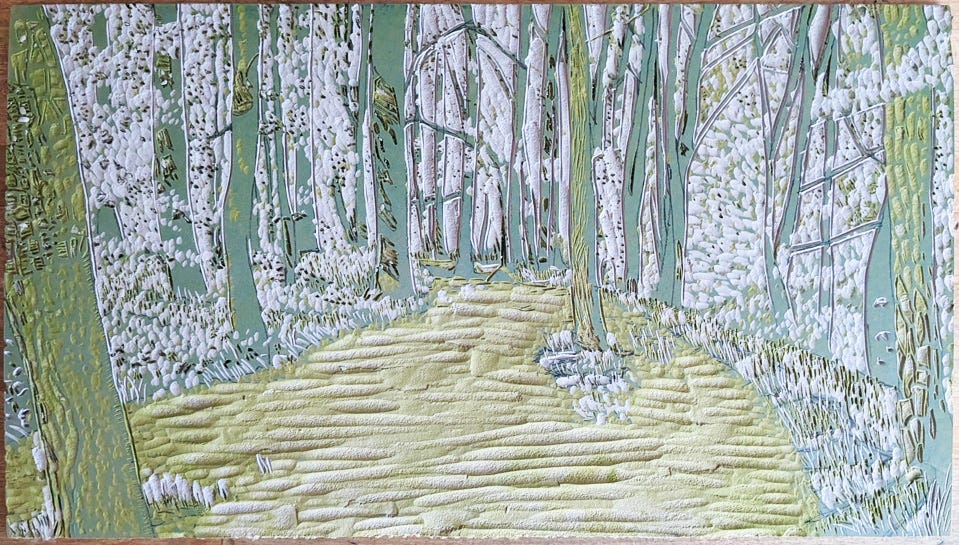

The picture at the head of the page is a block once it had had its final carving, ready for printing the last layer. The only bits still uncarved are those for a layer of translucent grey, which will darken the trunks and some shadows and leaves. The white bits are the most recent carving, while the more yellow cuts are from earlier layers and have been stained by previous inking.

Below is a very short video of the layers building up this print. The video starts after two layers had been added because I forgot to take a photo when I had done only the first layer of lilac ink in patches through a stencil. In total then there were seven layers of ink, though not all layers were on all parts of the block.

‘Bluebell Path’ is now drying on my print rack and will be available at York Open Studios and Printfest.

By the way, at a recent print fair I overheard a visitor confidently explaining to his companion that reduction linoprints are made by carving a block to different depths for different colours, “…so they carve deepest for white”. I’m not sure how he imagined that would work….but that isn’t it.

Saving Omai

I am always wary of the uncomfortably parochial overtones of something being ‘saved for the nation’, but I can wholeheartedly get behind an artwork being ‘saved for the public’. Currently Joseph Reynolds’ stunning ‘Portrait of Omai’ is in danger of being sold into private hands, either here or abroad, and never being seen by the public. The National Portrait Gallery, which would be the perfect place to display it, is trying to buy it instead. I have chipped in a little, with a rather more modest contribution than the suggested starting point of £50, and if you feel moved to do the same the appeal fund is still open. (See button further down).

Why I think it matters

This beautiful painting is one of the earliest English portraits of a person of colour. In fact I thought I’d read once it was the first of a named subject (as opposed to just ‘a servant’ or similar). However I can’t find that reference now so don’t quote me, and certainly the portrait of Dido Belle was painted at around the same time though no-one seems to agree exactly which year.

Painting different skin colours is not simply a matter of adding more white or mixing in a bit of brown; mid-tones, highlights and shadows all behave in very different ways. Bearing in mind that Reynolds’ entire previous portrait career, and more importantly training, was almost certainly spent painting white subjects, the way he triumphed here is a testament to his extraordinary skill, observation and mastery of his craft.

You can read more about the fascinating story of Omai (or Mai) and how an 18th century Polynesian Islander ended up in England’s high society here.

Shop closure

I’m off to visit family overseas so my online shop is currently closed for orders. It will reopen at the end of the month. I haven’t been organised enough to prepare a Substack post to schedule for while I’m away so I’ll see you when I get back.

All the best

Jane